All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

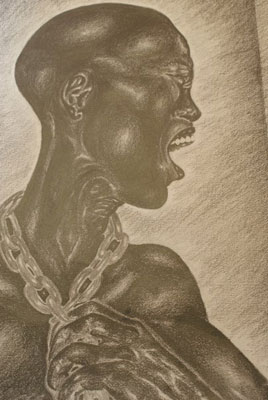

A closer look at the past in Toni Morrison's novel: Beloved

Everything changes with time. The same river as it was a second ago is never to be found. A cloud, once passed, can never again be recognized. People are no exception. In fact, nearly all cells in a human body get replaced within ten years, and at every second something new is inhaled and something old exhaled. Yet one can still tell a river is that river, his friend that person, and him still himself. Things seem to form their identity in the stream of time; although nothing ever occupies one same position, the past—where it had been, how it had drifted—makes one himself. In Toni Morrison’s novel, Beloved, the identity of Sethe is made by her tormented past as a slave. She tries to remove her past from herself, but she couldn’t do it without removing her identity as well.

Sethe is sold to the Garners family of the Sweet Home Plantation at the age of seven. In the dozen years as a slave, she makes a big family with the others. With the freedom given by the Garners and protection from the Sweet Home Men, Sethe has a mind of her own. She chooses for herself a husband who is most caring and generous, and even asks for wedding dress, which seems absurd given her state of slavery. Later, when the new cruel slave owner, known as Schoolteacher, comes and tortures the slaves, she resolutely escapes from the plantation to protect herself and her children, eventually making the long treacherous journey to Bluestone Road in Ohio.

However, after enjoying four weeks of freedom when her daughter, Beloved, dies, she begins to close herself from the past. Denver, the younger daughter, once curiously asks of the past, Sethe ends up revealing very little of it and leaves most to mystery. Sethe warns her: “Where I was before I came here, that place is real. It’s never going away. Even if the whole farm—every tree and grass blade of it dies. The picture is still there and what’s more, if you go there—you who never was there—if you go there and stand in the place where it was, it will happen again; it will be there for you, waiting for you. So, Denver, you can’t never go there. Never.” (Morrison, pg. 18) The past, Sethe believes, will forever stay even when all the materials that contain it disintegrate and have the same influence as it would before, like a river that would remain and flows as always, despite having no material components of the past. She distances her family from that memory, from the past that is herself, so that Denver won’t, and Sethe won’t again, be like an animal. And Sethe makes sure that her daughter never reaches that part of the past, not by being there, and not through her memory.

Sethe’s attempt to remove her past from the family eventually removes her identity as well. Facing the past is like tearing off dead meat from her wound, for which not only the process is torturous but also the result may be an even deadlier infection. Therefore, she develops an attitude of neither acceptance nor rejection, but extreme passivity, and keeps a distance from the past far enough only so she won’t have to face it. She uses this attitude for Beloved’s ghost, who has haunted the house at Bluestone Road for eighteen years. The ghost is “spiteful” and apparently harmful, which causes Sethe’s sons to leave and the house to be in isolation for eighteen years. Yet she does not escape, nor try to exorcise, nor give the ghost motherly love, but passively cleans after the mess the it makes. In fact, when Paul D., one of the Sweet Home Men, comes and reacts violently to the ghost, both Sethe and Beloved’s ghost react somewhat in shock, because no one has ever treated it this way. But as the girl that saved Sethe during her escape said, “Anything dead coming back to life hurts”, her wounds cannot be healed unless she chooses to face them. (Morrison, pg. 17) The passivity towards the past already becomes reflected on other things in life, a sign for the diminishing of her identity. When the engraver offers to carve Beloved’s tombstone in exchange for her body, she accepts and even regrets for not being able to trade for more words on the stone beside just “Beloved”. The same woman used to have to will and mind to walk from Kentucky to Ohio for the wellbeing of her family, but now she cannot think of another way for a seven-word-engraving besides prostitution.

Sethe has made a prison for both herself and Denver. The past is forever wed to her in one form or another, and she knows that well. But the past does not imprison her, it is Sethe, who knows that a chain can’t strangle her if she doesn’t escape, and makes prison walls to keep the family where it can’t see the past nor feel the chain, creating an illusion of freedom and normalcy. To keep the wall intact, she would accept anything, even prostitution, and gradually her “iron eyes” transform into “deep wells”, which shows the loss of spirit and desires (Morrison, pg. 4). For Denver, who is being raised this way, knowing her identity has also been difficult. Because of the inaccessibility of the past and isolation from the outside world, she comes to an understanding of herself that is dependent on ties with others, who, at first, are only Sethe and Beloved’s ghost. She reacts bitterly to Paul D.’s stay because he has taken both ties away from her, having chased off the ghost and sharing an intimate past with Sethe. But when Beloved’s reincarnation arrives, Denver is overjoyed, because she thinks she can build a unique and unbreakable bond with her, with which Denver be affirmative of her own existence, and later takes care of her and keep her darkest secrets. This dependency on other people’s reassurance is of same origin and nature with Sethe’s passivity towards life.

A river stops being that river when its whole entirety is devoured, perhaps by an ocean, and its flow never to be found; a cloud stops being that cloud until it breaks and rains down to become other things; a human is no longer himself upon death, when his conscious eternally lost and his time perpetually paused. Sethe and Denver have not died, though for eighteen years, time is paused and both have not moved on. But they are alive—living, flowing, and drifting—and no wound, no wall, and no chain can last forever. Even the deep wells of her eyes may one day be fed more than she can accept, which would not come as a surprise considering the arrival of the two uninvited guests. Everything changes with time.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.