All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

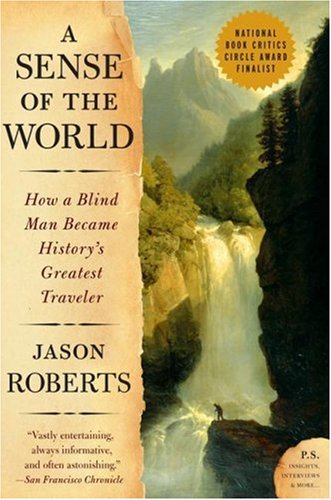

A Sense of the World by Jason Roberts

‘Now it was January [1831], high summer in Australia… [Holman] booked passage on the Strathfield Saye… one of the fastest ships on the route… During three months of uneventful sailing through the Tasman Sea, the Indian Ocean, and finally the Atlantic, there was one flash of excitement. During a provision stop on the isolated island of Flores, Holman and other members of a shore party found themselves stranded when a squall blew the Strathfield Saye to sea. They idled about for two days, taking bets as to whether they were now castaways. The ship, of course, reappeared to retrieve its passengers… In a typical fit of modesty, he described the now-resumed voyage as “not marked by any incidents worth noting.” In truth, it contained a milestone both personal and historic. Somewhere in the Atlantic, approaching England, Holman at last completed his circuit of the world [after thirty-three years of traveling].’ (p. 285)

In A Sense of the World, Jason Roberts details the extraordinary life of James Holman, “the quintessential world explorer: a dashing mix of discipline, recklessness, and accomplishment, a Knight of Windsor, Fellow of the Royal Society, and bestselling author. It was easy to forget that he was intermittently crippled, and permanently blind.” (Introduction, xi)

Inaugural winner of the Van Zorn Prize, Jason Roberts is a journalist and best-selling author. A Sense of the World, his most popular book, has many honors including being a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, a national bestseller, and being named A Best Book of the Year by six publications including the San Francisco Chronicle and the Washington Post.

Intrigued by a minuscule chapter on Holman in the insignificant Eccentric Travelers, Jason Roberts searched for information on the forgotten Blind Traveler. His three years of research are accumulated in this thorough biography, which documents Holman’s life from his birth to death and all of his adventures in between. Many first person sources, including an abundance of entries from Holman’s journal, make A Sense of the World a unique hybrid of a biography and a travelogue. Three hundred and fifty-seven pages long, and eighteen chapters, A Sense of the World is a completely engaging read.

Holman was born on October 15, 1786, in Exeter, the fourth son of an apothecary. In 1798, he entered the British Royal Navy and in 1807, he was named a lieutenant. Holman became afflicted by an illness that claimed his eyesight in 1810. At the age of twenty-five, he was completely blind, and despite his best effects to conceal his affliction, he was discharged from the navy. In 1812, Holman was accepted into the Naval Knights of Windsor and receives a pension, and lodging at Windsor Castle. Holman studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, but was unable to find any cures for his curious afflictions. He returned to Windsor, but finding his life tedious and dissatisfying, however, he escaped his uneventful duties at Windsor by embarking on journeys around the world, which he claimed are necessary absences for his health.

One can only wonder what the public’s perception of Holman was during his time. “In an era when the blind were routinely warehoused in asylums, Holman could be found studying medicine in Edinburgh, fighting the slave trade in Africa (where the Holman River was named in his honor), hunting rogue elephants in Ceylon, and surviving a frozen captivity in Siberia. He helped unlock the puzzle of Equatorial Guinea’s indigenous language, averting bloodshed in the process.” (Introduction, xii) Instead of shunning society and isolating himself, as would have been expected, Holman faced the world with a confidence that most “normal” people would have found astonishing. “He did not wear a rag around his eyes. Nor did he shirk from the gaze of others. When he ventured outdoors, he did so in full uniform, with as erect a bearing as his rheumatism would allow.” (p. 75) Most astonishing, though, is that Holman was able to write. By buying a “writing machine” called the “Noctograph”, an invention by Ralph Wedgewood which was designed for writing in the dark, Holman was able to record his adventures and produce manuscripts for his best-selling travel journals.

Despite his handicaps, Holman’s resume includes astonishing accomplishments, which, surprisingly, were quickly forgotten during his lifetime. This can be blamed mostly on the harsh critique from a caustic competitor of Holman, who wrote that “his sightlessness made genuine insight impossible.” (Introduction, xii) Unfortunately for Holman, this impression lasted with the public, even as he garnered respect from notable colleagues. “In The Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin cites him as an authority on the fauna of the Indian Ocean, In his commentary on The Arabian Nights, Sir Richard Francis Burton (who spent years following in Holman’s footsteps) pays tribute to both the man and his fame by referring to him not be name, but simply as the Blind Traveler.” (Introduction, xii)

Jason Roberts does a wonderful job in A Sense of the World of showcasing the determination of a great man who made the most of what he had, and who experienced the world with a heightened sensibility. He lets us enter Holman’s world by describing it in such rich detail, almost as if we are right there with him. The reader finds himself/herself drawn in by just the first paragraph. “The blind man paused to feel the end of his walking stick. It was scorched and blackened, a few moments shy of bursting into flame. He rolled the tip in the abundant ash to cool it, then continued his progress upward, toward the mouth of the volcano.” (p. 1) Roberts makes use of those three sentences to introduce to us Holman, his walking stick (which he used to “feel” his way around, and by tapping it on objects, he could calculate what was around him from the reverberations), and the amazing adventures that are in store.

Roberts also succeeds in illustrating the irony and dichotomies in Holman’s life. Holman is on one hand respected as an exceptional explorer, yet on the other, is accused of being a fraud, he was once a bed-ridden invalid who ends up climbing Mount Vesuvius, and he can sense an object without seeing it. As James Holman once ironically quipped, “I see things better with my feet.” By showing the contrasts that make Holman a unique person, Roberts invites the reader to see the depth of Holman’s sightless adventures.

I appreciate A Sense of the World because of its inspirational story of the Blind Traveler and the way in which the narrative unfolds. I think that we can all learn something from Holman’s journeys, trials, and tribulations. Jason Roberts brings the biography to life by showing the strength of the human spirit in dealing with a disability. It takes me back into time and makes me feel like I am right there beside Holman, traveling with him across the world.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.