All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Patent Leather Guilt

There is a rail wrapping around my porch, nice and shiny white. Safe. There is a rocking chair too. Old and scratched and warped. Like to feel the broken, stubble splinters grating against my back. There’s something floating on the summer evening air, something far and fleeting, caught and then lost again. It twirls, teasing, round the chair back and through its rockers, in the crevices of my elbows and the spaces between my toes. Whispering, cradling me. Where I have sat. For seven years.

Black-blue-brown night. Littered with stars and hopes. A knock at the door, hesitantly. My mother stiffens and leaps from the room, where she’d been reading me a bedtime story.

Soft little feet pad through the hallway behind her, curious feet. What made Mother stop reading?

A little girl. A mousy, brown-haired, tiny girl. Trembling, limpid eyes the color of the night, huge in a starved face. Ragged black dress eclipses her ankles and floats in sweeping folds of fabric around her knees. She clutches a beaten purple rabbit with no eyes and only one ear. Nothing else.

My father hears my carpet footsteps, grabs me. He carts me to the bedroom and dumps me on the bed. I turn my face up to my father, a confused flower opening towards a menacing sun. Whine, “Father, what’s that girl doing here? She ruined bedtime!”

A frown. “Fritz, the little girl is hiding from the bad guys.”

“What bad guys?”

Clouds scud across his face. “Anybody. Everybody. Don’t tell a soul that’s she’s here. Especially the men with the shiny boots and the badges. They don’t like her.”

“Why not? Did she do something bad?”

“No.” A heavy sigh. “She only lived.” Father’s face softens a moment, pensive, brooding, then hardens. “So you mustn’t tell anybody about her. Ever. Understand?”

“Yes, Father. I understand.” Of course I don’t. I am nine years old, and an idiot.

“And, Fritz—you’ll sleeping in the drawing room tonight. The little girl will have your room. She’s had a long journey, and we want her to be comfortable.”

What an injustice! Outrage! I hold onto the bedstead with all my might until Father peels my fingers off and drags me, kicking and screaming, to sleep on the bare carpet of the living room.

“I hate you! I hate you!” I shout at the little girl. Her eyes are like a punished puppy dog’s. They are led to my room, deep and silky, haunting.

I storm about the house for the next week, boiling with childlike rage. Don’t notice the lines on my parents’ faces, their haunted walk. Don’t care. My room is stolen, my second helpings devoured shyly but eagerly by an underfed mouth.

If children could hate, I would hate the little girl. She is always there, hanging listlessly in the doorway, slinking along the hall to the bathroom, vaguely clutching her bunny. A ghost of a child.

I steam as I sit in the classroom, not hearing the speech glorifying the war. Can only imagine the little girl playing with my toys, reading my books, being cared for by my other. The Führer’s prejudices are not mine, only the prejudices of a young boy. I wouldn’t care if the girl were a hideous monster, much less a Jew. All I know is that she is stealing what I love.

Dinnertime and our sullen foursome. My father kindly puts a hand on the little girl’s shoulder. She flinches.

“Honey,” he says gently, “would you like some nice new shoes to wear? Your old ones are getting a little worn out.” They are slips of cloth with barely enough on their soles to stay together. Just like her and 9.5 million others.

The little girl nods, her face pitifully hopeful. I am almost sorry for, until Mother whips out a pair of shiny black shoes. My shoes! Bought them just last month, for the Sabbath days. Better even than my toy soldiers. To be wasted on the girl?

I fling myself up from the chair. “You took my shoes!” I screech. “You and your stupid bunny! Stop eating my dinner! Stop sleeping in my room! Go away! Go away!”

Quivering, I grasp the back of the chair as Mother tenderly cradles the little girl, as she never holds me, crooning softly and shielding her from my tirade. Father hauls me to the bathroom by the scruff of my neck. Yells at me to come out when I can be civilized and generous to “our guest”.

I spend the entire night in the tub.

The next day at school the disguised cats, the Gestapo, come prowling among us innocent mice. Marching into the classroom, surveying their thirty good Aryan citizens. They smile benevolently on everyone and no one. I sit straighter in my seat. So confident! Strong! And the shiny boots like angels.

“Heil Hitler.” The pudgy Nazi proclaims. He beams at us from the height of five feet. “Now is the time to prove what wonderful students you are. Have any of your neighbors been acting suspiciously? Have you seen unknown person in their houses? Are your parents suspect? We’ll come around an ask each of you. If you have some information for us, it could mean a promotion in Hitler Youth!” He grins and walks the aisles of veiled interrogation.

There is no contest. I tell him everything. A pat on the back, another warming smile. “Thank you very much, young sir. We’ll get that friend of yours where she belongs. Heil Hitler.”

“Heil Hitler!” I chirp. What a nice man! Nazi eyes crease and snicker at the stupid naïve mouse.

Twilight. Sky the color of a bruise. The harsh slap is yet to come. I snuggle in my sleeping bag, dreaming of my own room. The little girl will go away, get a proper home where she doesn’t take anybody’s toys, or bed, or shoes. I know I did the right thing.

A flurry of knocks explode on the door at midnight. I jump three feet out of my sleeping bag, watching Mother and Father jump from their bed and fly to the little girl’s room. Rush out with the girl and stuff her in my sleeping bag.

“Sit by her, Fritz!” Father hisses. “Remember, she’s not here!”

Mother murmurs astonished niceties at the three soldiers, who have none of it. They are not the friendly, chubby men who came to Fritz’s classroom. Instead lean, lithe, and foreboding, not house cats. They are the ones who prowl in the night, harsh, scrawny, claws. Heavy brows and vicious mouths. Eyes burning with Führer fever.

“House search! Hide nothing!”

They ransack the two bedrooms, the kitchen cupboards, even the bathroom and Father’s carpentry bench. They stomp into the living room. Boots eyes mouths badges sick taste of fear rising in the throat.

I cower. Too big. Too mean. Wrong men. I will keep the little girl covered, I think. Wait until the nice house cats come.

But I shiver too hard, elbow catching the little girl in the neck. She gasps. And that is all it takes.

Alley cats pounce, and there is no evading their claws, their growls, frozen in time. They shake the girl out of the sleeping bag like so much dirty laundry, yanking her by the hand.

Her eyes scream. Beloved purple bunny dashed to the floor. Hair flying in panicked clumps, dress swirling, reaper’s gown. Giant eyes. Mournful, shrinking, dying.

They whisk her out of the room then, ho-nailed boots crashing on the trembling floor. She hangs between them, limp with fear, like one purple bunny lying crushed at my feet. Everything is right-wrong.

My parents were taken a week later, with barely a hug and a kiss. I never saw them again. Lived with my neighbor. Watched the war shrink as I grew. Decided to fall in love with one of my classmates. A swarm of happy, guilt-free Aryan children. One vapid lovely wife. A gnawing in my stomach until 1969.

Majdanek. The old concentration camp. A blonde family. The children played around the memorial, a pile of shoes six million tall. I, hunched, a hunger in my wilting cornflower eyes, walked slowly around the mountain, remembering.

Circled it once, twice. Stopped. Stared. Put my hands up to shade my eyes from the cruel and vindictive sun.

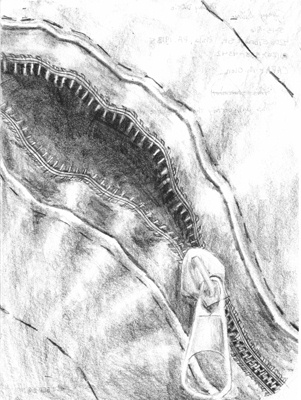

There was something dully shining, unlike all the other dusty hopeless souls. Halfway up the pile, balanced precariously on the edge, like the pair of dark deep endless eyes. Trim patent leather. My shoes.

No. Her shoes.

I made it back to my rocking chair before the tears started inching down my cheeks. They haven’t stopped since then. I don’t think they ever will.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 2 comments.