All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Machinery of Longing

They go home after, and Jean vomits in the kitchen sink until she's trembling all over. Then she sits at the kitchen table reading an article on the theory of relativity.

Tom slumps at his typewriter, staring blankly into the gray.

Later, they go out on the balcony and stand with their eyes tilted heavenward, stone-faced.

They do not speak to each other for exactly forty-two hours.

***

"You're making bread," Tom observes and leans against the door frame.

"Yes."

"Why?"

"Because I miss her."

"So do I, but I don't see the benefit of expressing those feelings through culinary endeavors."

Jean pauses and wipes a smear of whole grain flour from her brow. "My grief isn't like yours. Never has been."

"I know," he says, and doesn't try to placate her. "How is this helping?"

"My grief is like a messy, bloody hurricane. It manifests itself more as fury than anything. Kneading dough makes me feel less like I'm going to rip someone's head from their spinal cord."

"Point taken."

"Think she'll call tonight?"

"Wouldn't bet on it. She has homework. Friends. Life to attend."

"Still," says Jean, egg yolk and milk spattered on the counter, still, and her heart slips to the right.

"Still," Tom agrees.

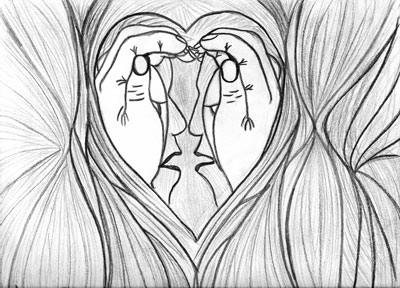

They look at each other, joined, a pair of metaphorical handcuffs chaining them together. Pain, consummation, something that changes lives, something indefinable, something radiant and raw.

They look at each other and they see the whole world built up and they see the whole world fall again. They are drenched in it, if the It had a name, if the It was something they could describe beyond a bodily ache and a gnawing of the gut and a bright, shattering loss.

Victims of amputation often describe feelings of pain in the empty space where their limbs once were, as though the bone and blood and skin and muscle still remains, as though they are not missing a part of themselves. Phantom pain, doctors call it. The mind is powerful. It creates sensation where there is no matter. But what, some might ask, happens when the heart is the severed limb? When it sprouts legs and crawls out of the chest in pursuit of those it holds dear? Can't live without a heart, can you? No. You cannot.

"Hand me the spatula," she instructs.

"Alright."

He comes over. Hands her the utensil. They stand together, shoulder to shoulder, and Jean dusts him with cinnamon, and he hiccups with laughter, and they lean together, breath staining each other's skin.

"We're so strange," she notes, when their foreheads are brushing and she can make out the little perambulating nebulae in Tom's eyes. She feels guilty. They shouldn't be laughing. Not when their daughter's gone for what feels like eternity and they have to re-learn how to breathe.

"Has it really taken you all this time to realize that?"

Jean kisses his hairline, his cheekbones, his chin, his neck. She's never been a religious person—science and logic and fact are her tools—but this is as close to supplication, to prayer, as she has ever come, nose buried in his hair, fingers fluttering at his shoulder blades. She looks at Tom. There's a certain way you treat all the simple things in the world that is entirely obscene, she thinks. Like the way you straightened your necktie the first night I ever wanted to kiss you, or the way you grip your coffee mug, or the way you've wrap my heart. You treat them as if they weren't simple things. And they are, Tom. They are.

"It has," she whispers and closes the gap.

***

"I've interrupted you," Jean says, stumbling into the den three nights later with an ashen face and lips pressed tight. "I'm sorry, I didn't mean to, it's just…"

"All right?" Tom glances toward the bathroom. He feels like he is going to be sick.

Jean stares at him. Her pupils are cesspits of darkness, flecks of mud and murk in the irises. No order, no hospital corners. Just chaos.

"You're not alright," he concludes.

"I'm—"

Tom presses a hand to his forehead. Feels the saga that began with his daughter's birth conclude itself in a fierce burst of pain that makes itself known in the most ridiculous places: his jaw, elbows, kneecaps, skull, toes. He feels it in his elbows. Absurd.

Jean begins again: "There's a word for children without parents, but there's no word for parents without a child." She laughs, a harsh and terrible gurgle in the back of her esophagus.

Tom does not say anything. His heart kicks loudly.

"S***," Jean murmurs. It's a shock to his system. In all twenty-one years of marriage, his wife has never cursed. Then louder, "Damn it damn it damn it damn it I cannot breath I cannot sleep I can't think I cannot make myself feel like a real person because all I am anymore is plastic and it's making me want to—"

He shoots to his feet as though he's been shot, circling his arms around her trembling body, lowering them both to the threadworn carpet and rubbing his thumb along Jean's occipital bone as they sob, soundlessly, without finesse or dignity. Wrenching to the point of revulsion.

"Oh, god," breathes Tom. "Oh, god."

Jean turns her face to the wall. "What can we do?"

"We can't do anything."

And that's the whole truth of it. There are certain kinds of grief in which no empathy is adequate. Hands grasp, hearts bleed, words fail.

Explosion: starts on the inside, pushes outward in a rush of pure anguish. Crying. Possibly shouting. Sound vanishes into the whiteness.

The universe rearranges itself.

***

"You know, I never thought life would be like this."

Sluicing water hits dirt and Jean opens her umbrella, studying her husband with a dull ache in her chest. Long and hard and sad as hell is what he means, probably. A superfluity of sobering truths, reality created from disparate pieces.

"I thought," Tom blinks as raindrops cling to his lashes, "I thought—I don't know." Tom, the master of unfinished locutions. "I…"

Which is the shortest sentence Jean's ever heard. Barely a sound. Air passing over vocal cords. Vibration.

At last Tom finds his way to the point: "I guess I thought would be more elegant."

"Like your poems?" She flashes him a deeply sardonic look.

"Right, but he thing is, it's not." A pair of school children dart past, splattering the couple's ankles with mud. "Existence isn't half as exquisite as I make it out to be in writing."

"Well, you've always seen the world through a lens of…" Jean pauses, grappling for the right expression. "Wonder."

"That is precisely why it hurts me so much more than other people when things don't turn out. I believed in magic."

"I believed," Jean mutters, inhaling sharply, "in logic. And I assure you, it's a far crueler letdown."

Her heart, grown to be fruit of the season, needs more time, more sunlight.

She can't pick it, can't bite it, can't taste it, but she can feel it. Feel it unripe. Because it's too early. Because, as with everyone, she has to survive the summer, she has to survive that in order to be able to understand, to be able to dare. Because until you brave the heat and the exposure and the nakedness, you don't know what summer is, what summer brings. Summer brings [poor Jean, unseasonal, harried Jean, absolutely unaware of this] the blossoming.

***

And sometimes, on nights dark as the wolf's mouth, Tom's sister rings him up and he eases out of bed and tiptoes up to the roof where he can breathe deeply and study the stars.

"Love all of this," Tanya says, voice cracking in places.

"Hmm?"

"Just, just. Just please."

"I'm doing my very best, Tanya, I am, okay, I am. Is everything alright?"

"Everything's coming up roses, brother."

"You've been awake for about thirty hours straight, haven't you?"

"No. Just thinking."

"It's late. You should sleep."

"Can't."

"Never too old for counting sheep, are you."

Tanya bursts into an ineloquent jumble of laughter and something sadder and Tom thinks, my god, is everyone on this earth insane?

He laughs too, harder than he'd have thought possible. Standing there overlooking the glittering metropolis, so very full of electricity, blackness, potential, love, all of which goes further than the elastic limit of the soul. He could scream and yell and shout with it, set his vocals cords aflame and his voice scattering; send a bright blade of vibration into the roar and let it travel out and out and out into space and onward and onward, continually, continuously, infinitely. The splendid lunacy of it makes his heart beat as a deer heart, wild and fast and empty of malice.

"Try to be alive," Hemingway said once. "You will be dead soon enough."

Tom tips his head back, howls.

***

Jean joins him in the courtyard later and catches him in her arms, her fingers spasming on his shoulder blades, his nose pressed against her jaw, twined around each other as though all space between them is agony.

"What goes down must come back up," she whispers into his skin.

Tom only groans, high and rough, the way he does when he's holding back tears [and she should know].

***

The next time they see Clara—the three of them crowded around a tiny café table in thin November sunshine—Jean watches her daughter's face, looks at the pale contours and pastry crumbs on those rosy lips and desperate way her entire person seems to be shivering, twitching, clamoring toward the light of the world. And then Jean turns her head and sees how Tom doesn't notice any of this.

But mother sees daughter, and thinks: Hope made flesh.

"I'd like to go for a year abroad," Clara announces.

A pause. "Then abroad you shall go," Tom laughs, and Clara beams.

On the periphery, Jean fumbles around for something to clutch onto because it hits her then that this is truly the end of an era, and that notion is fast becoming the matrix of her agony.

Clara looks toward her, the little quirk of her lips and look of honest anticipation a silent plea for approval. Jean nods, smiles [she is Alice, falling into the rabbit hole]. A familiar violence rises up in her, born of total helplessness.

"You'll have a phenomenal time," she declares, resolute, and there's a whole world of feeling in these words.

"Thanks, Mom."

"Yes," says Jean. Her stomach swims, eyes burn.

…

"Oh," Tom breathes, staring into the Manhattan bay. It's a blinding afternoon.

"What?"

"It's a great nothing."

Jean frowns, uncomprehending.

"I mean, it's a void. A vacuum. Where there should be something, there's…" He shrugs ruefully. "There's just a great nothing. It's never looked like that before."

Jean looks like wants to make a remark about the way humans project their emotions on neutral images, but doesn't. Tom wonders if she feels it too. The numbing beauty. The loneliness. He turns, studies her: the halo of eyelashes, the slope of her nose, the cobweb of lines carving themselves into her skin, new and quiet.

She pokes a decaying seal corpse with a stick.

They watch the water.

…

Jean and Tom have been happy in their lives, but they have also been ravaged by loss, the wild violence of human grief.

They fill these bruised, stinging parts of their hearts with the pressing of bodies to bodies, of mouths to ears, of mouths to mouths. They lie on their mattress, an honest entanglement of arms and legs. Thinking. Over the way things subsist and shatter, bloom and wilt, rise and fall, sparkle and fade, dominated by the whims of an indifferent universe.

Over the rapid, precious flight known as being alive, the thought of which glints brilliantly.

Feet twisted together on the over-worn cotton of their bedclothes, Tom says, "I wish it wasn't so hard."

"Yes," Jean agrees, simply, and they do not dwell on it.

***

"Move with me," says Tom and there is no music but Jean takes his hand and looks into his eyes, unshaken, and she moves with him.

Hearts beating in tandem, pulses synchronizing, they sway, shuffling in a waltz inaudible to the rest of the world.

"You are—" Tom begins, and never finishes the phrase. It hangs, without conclusion, fading into the stillness by which they are surrounded. Jean rests her palm on the back of his scalp, fingers sliding through close-cropped brown hair.

She is engulfed in a warm, scarlet pulse of rhythm. His aftershave invades her airways, painfully familiar, makes her stomach swoop.

Breathe," she commands, and maybe it's more for herself than him but still he inhales, gasps, tightens his hold around her waist.

A hand slides up her back, a set of knuckles grip tighter, turn white "Stars and midnight blue," he chokes out, looking at her mouth. she frowns, questioning, but he kisses her softly and says, "Nothing."

"Move with me," he repeats.

"I am."

"Like this." Then they are spinning round the room and all time and space is nothing more than a washed out blur and Jean is gagging on laughter and tragedy, nauseous with the mixture of it. Inhale, inhale.

They trip unwittingly on the foot of an armchair.

"Never could get the hang of a waltz, could we?" Tom is rueful, beautiful.

"No reason not to dance." She brings her hands up to cup his face, precious fragile being that he is, and sees herself in his glistening irises, sees the devotion there, absolute.

"Jean—"

"Wait." She tugs him along and they sail past windows, past framed photographs, past material objects that hold so very little significance anymore, and she says, "I am, I'm moving with you, see?"

And this time he does, shaking with emotion not to be defined, at his wildest reverberation, that lovely scarlet lipstick she wears now smeared along his lower lip, eyes beyond depiction—like that of the scales on fish that swim in the sky—drawn into her torrent, the point of no return, the overflow—

"See," she echoes, gritting her teeth against a sudden sharp taste of burnt copper, and he opens his mouth, says, "I love you, I love you, oh," and they move, they dance.

***

Their joy is more ephemeral now and their hearts not so full of vigor as they once were, it's still beautiful. What they have together. This, the totality of their union. It's still warm and reckless and glowing, a tumble over an inestimable abyss, a single burning flare, a mad rush of electrifying gratitude. The water has closed over their heads, but they've come up gasping. Found out, well, what it's like. To be in the body, alive. Learned that yes, they can do what people do, which is love and drown and die and even then—it goes on.

This is gravity enough.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

Preferences

English

Deutsch

Español

Français

Italiano

Português

???????

Preferences