All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Two Roads MAG

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth …

-Robert Frost, “The Road Not Taken”

Her room smelled pungently of orange zest, but the acidity masked something musty beneath. She was hiding something, always. She kept a sleep journal, and each time she left to make tea in the basement kitchen, industrial sized mason jars in hand, I’d flip through its pages and familiarize myself with her nightmares.

Willa stayed awake into the witching hours of the night, diligently completing problem sets, only to put off sleep a little longer. After she completed her homework, around midnight or one o’clock, she laid out her clothes for the next day, mostly shades of blue, completed with her gray Birkenstocks, so worn in the soles that she slipped across the ground as she walked. Next, she chronicled her day in Moleskine notebooks hidden in her bookshelf behind Macbeth and The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Collectively, I must have spent hours poring over her notebooks while she showered or comforted an anxious freshman down the hall.

After she journaled, Willa wrote out a To-Do list in blue and green ink on a whiteboard on the wall. The lists didn’t change much day-to-day. Several newspaper articles always topped the list, followed by reminders to call Daddy and Mom. When her To-Do list was laid out to her satisfaction, she climbed into bed to read. At this point, the hour had usually crept to 2 o’clock. She slept fitfully for a few hours before rising with the sun.

Willa was built like a turnip, stout and balled-up, rigid with muscle. Her hair, always slightly greasy, fell uneven and long across her prominent shoulder blades. My dorm room haircuts did not suit her, mostly because her scissors were hopelessly dull. She displayed her taut stomach with short, flowy tank tops and adjusted for the winter with a ratty, pilly cardigan in some shade of taupe.

On Thursdays, we burst out of Mr. Hiza’s physics class and flew across campus to the farmers’ market, hoisting our heavy backpacks up by the straps to give our shoulders respite from their weight.

“6:02,” Willa said after glancing at her battered watch. We thundered down the granite stairs separating the North Side quad from the town center, weaving between sweaty members of the crew team headed to the dining hall where they’d pile overcooked broccoli and rubbery chicken onto their plates. We reached the market as the vendors were packing their zucchinis and strawberries into cartons stacked in the backs of their pickup trucks. Catching sight of us, the self-proclaimed “Soup Guy” pulled the lid off of his vat of chili as we brandished our dollar bills at him. As he ladled generous scoops into large paper cups, we laid three dollars each on his folding card table. We plopped down on a weathered bench, shifting our thighs to avoid the splintered sections. The sun danced across the glassy expanse of the Exeter River and hit my eyes like darts. Ducks slipped across the water, webbed feet beating invisibly beneath the surface, ripples spreading from their chests in expanding angles.

“This is freedom,” Willa said. I took another bite and turned it over in my mouth for a moment, swinging my ankles just above the grass. I decided that my disbelief in free will was a conversation for another day.

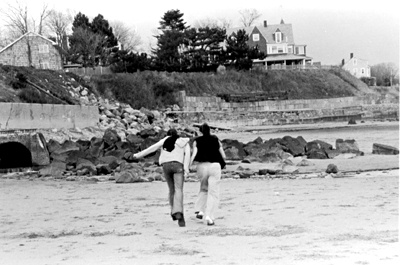

On Saturdays, we called up my quirky Aunt Tracy, who drove from Rye to whisk us away in her cardinal-red Honda Pilot. We flopped onto the sandy car seats and listened to 106.7 “The River” as the wind whipped through the open windows, stung our cheeks, and caught our long hair up in little cyclones.

Tracy smelled like the bread aisle at the grocery store and men’s deodorant. Everything she owned was red: red pots and pans dangled from a sagging wire strung across her kitchen, red stools stood beneath the countertop and served as ladders for red ants crawling toward a bowl of plump cherries. Out in the yard, red bicycles of varying sizes and states of decay marched through uncut grass and wild clumps of raspberry bushes.

Tracy often took us to her store, a rickety little flower shop squeezed between a fish market and a thrift store, and let us pick out bouquets for our rooms. “You could use a little sunshine,” she’d explain, patting us on the behinds. The blooms exploded out of vases, baskets, and buckets. Stray leaves of every hue and texture carpeted the slick floor and piled up on countertops, furry lamb’s ears and waxy holly exchanging pleasantries beside the cash register. I picked sunflowers, reliably jovial, while Willa picked shy peonies, hopeful she could coax them to bloom before they inevitably wilted. By the next excursion to the store, the previous bouquet had always shriveled and died, no matter how much sunlight it was exposed to.

“Something in the air,” Willa would say.

“Something in the water,” I’d shoot back. “I bet we’re wilting, too.”

We ate watermelon on the beach, juice running down our bare arms and dripping from our elbows into the sand. Tracy reclined in a beach chair in a black swimsuit that was stretched and worn to transparency at the midriff. Willa crashed through the frigid waves and hollered at the seagulls and sandpipers, and I crawled up and down the beach in search of sea glass for my collection. The sky, powdery cornflower blue, mingled with fleeting white caps, the fusions joining and breaking in an instant. Rocks and shells glinted like stars as they rolled across the cool sand into the shallows. They tumbled along the rivulets in the sea floor created by the currents’ pushes and pulls. Cold and clear, the water had no secrets.

At the end of the day, we watched the sun bleed across the sky like watercolor paints; pinks, purples, and peaches blossomed across the horizon as the daylight evaporated until only a hazy, magenta glow remained.

“Red skies at night, sailors delight!” Willa quipped. We pressed our bare feet together, our skin hot and itchy from sunburns.

Each weekend, we’d escape from the confines of our grade point averages and looming newspaper deadlines for a few brief hours, but our conversations inevitably drifted back to responsibilities. As the sun loped toward the horizon, Willa would pull out her battered planner and sigh as she perused her homework plans for the night. I’d log into the week’s newspaper spreadsheet on Tracy’s desktop computer and widen my eyes as I counted the articles next to my name. “Eight thousand words by Tuesday!” I’d shout across the kitchen.

“That’s barbaric,” Willa would reply without lifting her eyes from her notebook.

We bridge-jumped in May when Tracy couldn’t get out of work. We left our dorms at five, as soon as the doors unlocked, and scurried across campus amidst girls sneaking off to boyfriends’ rooms for a few hours before the dorm parents woke up. Main Street, illuminated by the buttery light of the rising sun, remained delightfully deserted as we scampered across with beach towels dangling from the crooks of our elbows. Upon reaching the bridge, we spread our towels and jackets on the cool pavement and clambered up the concrete barrier on shaking legs. We clutched hands and stared down, suspended 15 feet above the dizzying, murky water.

“Let’s pray,” Willa said.

“I don’t believe in God,” I said.

“So pray to the river and the sky and the trees,” she said. She shut her eyes and I followed her lead. As the sun’s muggy heat baked my shoulders, I came to understand religion. Willa slipped her short, bony hand into mine and began to count down from 10. I joined her at six, and then we launched into air, hanging, for the briefest moment, in freedom.

Our hands broke apart as we hit the surface and plunged into the darkness. The frigid water ripped the air from my lungs and clung to my arms and legs, pulling me down like an anchor. I grabbed at the water, seeking a nonexistent hold with which to pull myself to the surface. As my lungs tightened, I burst into the air and gasped like a fish, rubbing the water and silt from my eyes and blinking rapidly against the sun’s blinding light. I turned myself around until I found Willa bobbing a few feet away, cackling with joy as she floated on her back. Her pajamas clung to her body and her hair spread around her face like a fan, tugged this way and that way by the slow, lazy current.

I leaned backward until my toes and knees peeked out of the filthy water.

“Think there are fish in here?” I asked. Willa hummed a noncommittal response and propelled herself a few yards with a big kick. She flipped over to her stomach and allowed her legs to sink until she was treading water.

“Can you even believe that this place exists within our school? It’s so serene,” she mused. “It feels so far away.” A breeze surged through the trees and shook seeds out of the maples, sending them spinning down into the river like falling parachutes.

“I wish that we could just live in this moment forever,” I said. “I wish that we didn’t need to go back to our rooms and cry over problem sets.” Willa began to meander toward the shore and eventually hauled herself up the bank. She reclined against the trunk of a sturdy oak and folded her hands across her stomach. She tucked her sopping hair behind her ears and traced shapes in the dust with a pruned fingertip.

“If I were picking one to live in forever, I wouldn’t necessarily choose this moment,” she said after a minute, “but I understand the sentiment.”

“So which moment?” I asked.

“It’s not just one. I think it’s … I think it’s driving to your aunt’s house, before I start thinking about coming back.”

I pushed through the water with my chin skimming the surface until I had joined her at the bank. Wringing the dirt and water out of my hair, I settled myself beside her and pulled my knees into my chest. Goosebumps exploded across my arms as the breeze whistled across my wet skin.

“Can I tell you something?” I whispered, avoiding her wide-eyed gaze.

“Anything,” she replied.

“I’m not coming back next year.”

“What?” Willa’s shriek pierced the quiet of the morning and rang across the river. “What do you mean you’re not coming back next year? You’re leaving me here alone?” Her voice, high and shaky with panic, made my face flush with shame. I felt itchy and hot, goosebumps dissipating as her anger washed over me. For the first time, I considered her selfish. How could she receive such ground-shattering news and apply it only to herself?

“This wasn’t an easy choice,” I insisted, still staring out at the fields. The morning fog remained hung over them like a raincoat, sparkling as the sun beat through the haze. “It’s my parents. They know how unhappy I am.” She buried her face in her hands and exhaled sharply.

“I don’t want to leave,” I insisted, trying desperately to get her to look me in the eye.

“Then stay,” she hissed. She pushed herself up and stormed away, leaving her jacket and towel piled up on the bridge with mine. I let her go. I was ashamed that I had given up, that I couldn’t stand two more years, but beyond that I felt a weighty, stifling guilt for abandoning my best friend. Yellow blossoms waved at me from across the river, but I averted my eyes. I took a deep, shaky breath and pressed a blade of grass between my fingers. Raising the green sliver to my lips, I blew gently. A flat, wavering tone emerged from my hands and joined the quiet chorus of birdsong and cicadas. My eyes began to water, but I rubbed them, hard, with my knuckles.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 1 comment.

A reflection on a friendship strained by a transfer of school.